New space missions will probe the mysteries of Venus and the universe

A satellite designed to study Venus from top to bottom and a trio of gravitational wave-surfing spacecraft are two of the latest missions that the European Space Agency has adopted.

The agency previously had selected the missions, but the official adoption process means that contractors will be chosen so construction can begin to bring the mission designs to life.

ESA will partner with NASA for both missions, which will launch from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana in the 2030s.

“These trailblazing missions will take us to the next level in two extraordinarily exciting areas of space science and keep European researchers at the forefront of these domains,” said Carole Mundell, ESA director of science, in a statement.

A new voyage to Venus

The EnVision Venus explorer will study that planet in unprecedented detail, from inner core to the top of its atmosphere, to help astronomers understand why the hot, toxic world didn’t turn out like Earth. Venus is similar in size and distance from the sun when compared with Earth, and some researchers believe the planet might have even had an Earth-like climate at some point.

But “Earth’s twin” is now an inhospitable world, with surface temperatures capable of melting lead and intense, crushing pressure as a result of a runaway greenhouse effect.

Scientists hope the mission will answer key questions about Venus, including how the world evolved over time and if it ever had oceans, how geologically active it is and why the runaway greenhouse effect began.

EnVision is expected to launch in 2031 and will be the first mission to gather data on how the Venusian atmosphere, surface and interior interact. The mission builds on ESA’s first spacecraft sent to map the planet’s atmosphere, Venus Express, which orbited Venus from 2005 to 2014.

After a 15-month journey to Venus, EnVision will spend 15 more months orbiting the planet and flying through its atmosphere.

The satellite will have two deployable solar arrays and will carry a suite of instruments that can observe the Venusian surface and atmosphere as well as probe beneath the planet’s thick, obscuring clouds with radar and radio wavelengths.

It’s one of several missions in development to study Venus, including NASA’s DAVINCI and VERITAS expeditions set to launch within the next decade.

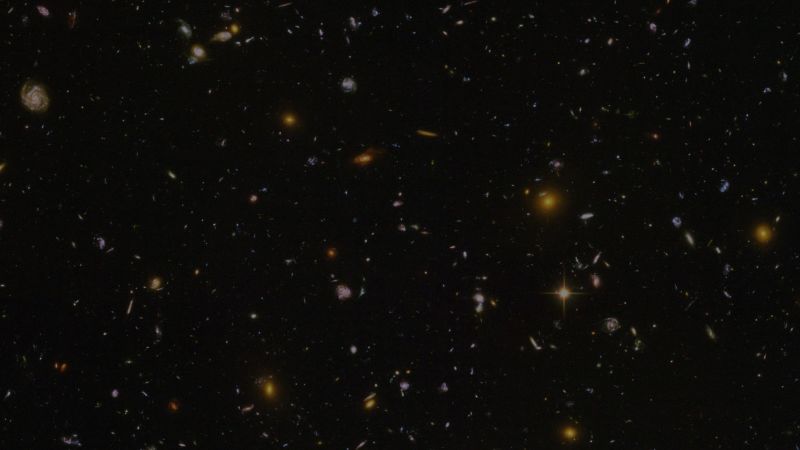

Unraveling the history of the universe

When massive celestial objects such as black holes collide, they send out ripples called gravitational waves that spread across the universe and reveal information about its history.

These waves have been detected with ground-based observatories, but the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, or LISA, will be the first space-based observatory to study the cosmic phenomenon. Ground-based observatories are limited in what they’re able to detect based on size and sensitivity, so they can only pick up on high-frequency gravitational waves.

But a space-based observatory can be much larger, and LISA will be able to detect waves that range from tiny to giant as well as low-frequency ones emitted by supermassive black holes that merge at the centers of massive galaxies.

The LISA mission includes three spacecraft that will fly 2.5 million kilometers (about 1.6 million miles) apart in a triangle-shaped formation. Free-floating gold cubes within each spacecraft will be used to detect gravitational waves.

The mission was born from the success of LISA Pathfinder, which ESA launched in 2015 to demonstrate the technology that the LISA mission will rely on to search the universe for cosmic ripples.

The new mission will look for evidence of black hole mergers across the universe, study the formation of thousands of pairs of stars called binary systems, peer inside dense star clusters within galaxies and try to measure the rate at which the universe is expanding. And LISA will be used to study the history of the universe by locating the first black holes ever formed after the big bang.

Together, the three spacecraft will fly behind Earth as it orbits the sun, about 50 million kilometers (31 million miles) from our planet. The agency expects the mission to last four years, with the possibility of extending it.