After two years of far-right rule in a Michigan county, one chance to change it

PARK TOWNSHIP, Mich. — For much of the last two years, American politics at its most divisive, ideological and angry had dominated the previously unremarkable work of county government in the place that Jim Barry called home.

Now it was primary day, and the voters of Ottawa County, a fast-growing, middle-class community of about 300,000 people on the shores of Lake Michigan, were headed to the polls.

Barry, who described himself as a moderate in the mold of former president and Michigan Republican Gerald Ford, was running for a seat on the 11-member county board and hoping that voters in Ottawa, which former president Donald Trump had carried in 2020 by 21 percentage points, might be ready to embrace a different kind of politics.

“I’m not sure Ronald Reagan could pass some of the conservative purity tests in the modern era,” Barry said.

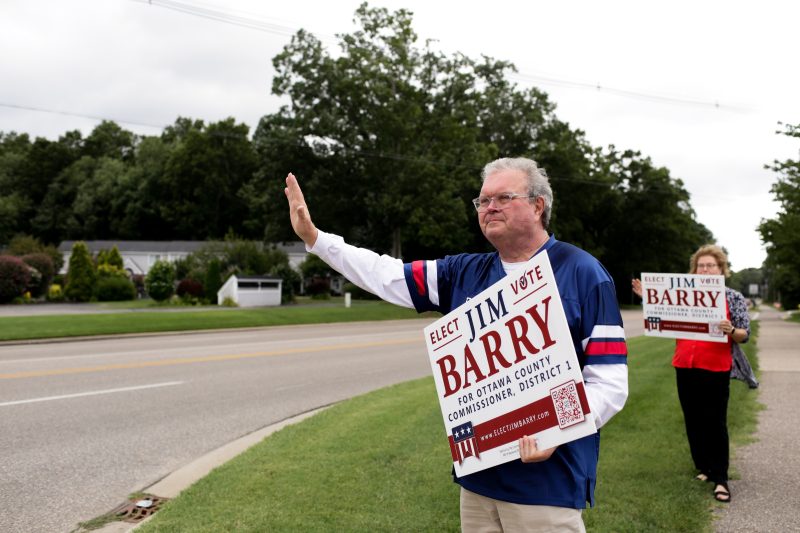

He was standing on a busy street corner wearing a red, white and blue football jersey that said, “Elect Jim Barry,” and waving a sign with the same message. Some drivers honked and gave him a thumbs-up. Others scowled. His wife thought she spotted his opponent, who lived nearby, amid the thrum of traffic.

In 2022, eight hard-line Republicans, channeling Trump-style anger over pandemic-era mask mandates, had won seats on the board, defeating more moderate GOP candidates. The new commissioners had swept into office promising to “thwart tyranny” and defend the county from dark forces that had supposedly infiltrated their local government to promote abortion, sexualize the county’s children and corrupt its deeply held Christian morals.

The transformation made Ottawa a case study in what happens when local government is buffeted by the same ideological battles and dissolution of trust that have afflicted national institutions for much of the last eight years. In a series of stories over the last 18 months, The Washington Post chronicled the changes in the county.

Board meetings, which had once been sleepy affairs, often stretched on for five hours or more as residents lined up to deliver their views on the Bible, drag-queen story hours and the safety of vaccines. The majority’s beliefs had shaped policy, with real-world impacts on the lives of Ottawa residents, and spawned costly litigation.

Two years after their stunning victory, the far-right commissioners were running on a simple rallying cry that spoke to their fears for their country and community: “Protect the Kids.”

Barry, a 69-year-old real estate agent, said he understood why so many in the community had been upset by the mask mandates. But he didn’t believe county government was the place to wage heated battles over divisive national political issues, like abortion, racism and sexuality. Instead, he wanted the county government to return its focus to issues like water quality and the high cost of housing.

“It’s not as exciting as trying to do something about transgender athletes in high school sports,” he said. “But there’s no purview for the county board of commissioners in that.”

Barry, who had been standing on the side of the road, off and on, since 7:30 a.m., checked his watch. “We’re coming up on 6 [p.m.],” he said. It was almost time to get ready for his election night party.

After all the turmoil and county board meetings in which neighbors regularly called each other fascists, communists, Nazis and Christian nationalists, Barry wondered if there was a way to pull back from so much of the vitriol consuming the country. In a few hours, he and the people of Ottawa County would have their answer.

A ‘God-briefed’ candidate

Twenty-five miles to the east, on the opposite side of the county, Rachel Atwood corralled voters outside her polling place. She was part of the slate of hard-line Republicans trying to keep control of the board. Her group, Ottawa Impact, dominated the county GOP.

“Do you need a Republican voter guide?” she asked as people passed by.

Atwood, 43, got involved in county politics because she believed that mask requirements were hurting her autistic son at a critical moment in his development. The mandates were over, but Atwood thought that the threats to her children’s well-being from the government and pro-LGBTQ+ liberals remained as real as ever.

“What makes me a little different in this race is that my experience is much more geared toward the current culture war,” she told a local television station.

She was running in the Republican primary against John Teeples, a retired attorney, who described himself as a “fiscal conservative” intent on restoring “kindness” to the county’s politics.

The night before the primary, Atwood and the other Ottawa Impact candidates each occupied one of the four geographic corners of the county and prayed for the protection of their community. Her skin was deeply tanned, the product of knocking on more than 2,000 doors — an experience that she described as transformative.

“God has been sending people to me through door-knocking to say things to me that are supernatural, that are God-briefed,” Atwood said in a recent Facebook live video from the campaign trail. She prayed with dozens of people who had autistic children or close relatives with the condition, she said, and promised them she would fight for more county services for their loved ones.

Atwood also said she had encountered constituents who told her they were exhausted by the infighting in the county. On their first day in office, the Ottawa Impact commissioners had fired the county’s administrator, canned its lawyer of 40 years, closed its diversity office and dumped its motto “Where you Belong” in favor of “Where Freedom Rings.”

More change — which Ottawa Impact opponents called chaos — followed. The new commissioners forced the county’s longtime sex educator, who had developed successful programs to lower teen pregnancy and curb the spread of sexually transmitted infections, into an administrative job. When their efforts to remove the county’s public health director were blocked by the courts, they cut the health department’s budget, eliminating a program that helped feed 22,000 low-income residents each year.

They turned down millions of dollars in federal and state grants because they came with conditions that the commissioners said were unconstitutional or immoral, and they became embroiled in a spate of lawsuits alleging discrimination.

Joe Moss, who co-founded Ottawa Impact and chairs the county board, didn’t respond to a request for comment. In an interview with a local television station, he described the new board members as regular people — teachers, entrepreneurs, nurses, social workers — who were acting as “guardrails” to defend the county’s children from “dangerous and harmful” forces.

Atwood disagreed with those who insisted that Ottawa Impact had hurt the community by introducing anger and division into the otherwise mundane world of county government.

“I’m happy people have become so engaged,” she said.

Outside her polling place a couple of supporters approached her and asked for a selfie. Atwood smiled and posed alongside them. “We’re praying for you,” they told her.

An anxious wait

That evening, candidates and their backers gathered at election night parties where they compulsively checked the county’s website for early returns.

Barry waited for the results with Rep. Bill Huizenga (R), the local congressman and his half brother, who had rented an event space at an upscale waterfront restaurant. The siblings stood together near the restaurant’s deck as the sun set over Lake Michigan, smartphones in hand.

Just after 9:30 p.m. the county clerk sent a text alert that early results were in, prompting nearly 4,000 people to ping the county’s website within 30 seconds. The flood of traffic crashed the site.

“We are aware of the website issues,” the county clerk posted on his social media pages. “A lot of folks interested in our results!”

The primary’s unusually high stakes made for unusual alliances. An older man in a red “Make America Great Again” hat sat with friends at an election night pizza party for Mark Northrup, a small-town mayor challenging Moss in the Republican primary. A few feet away, Jacqui Poehlman, one of Northrup’s volunteers, hunched over a computer with a “Bans off our bodies” sticker on it.

Northrup, 66, described himself as a “pro-life” Republican who planned to support Trump, his party’s candidate for the presidency. Poehlman, 43, described herself as “very liberal.” But they shared views on the value of well-funded public schools, the need for more affordable housing and the necessity of preventing Ottawa Impact from retaining its majority on the board. Both fervently believed that scorched-earth political warfare, which had become the standard at the national level, was causing irreparable harm when injected into their otherwise peaceful and prosperous community.

“Trump is his guy in the fight,” Poehlman said of Northrup. “But we’re not voting for Trump at the county level.”

At the Ottawa Impact party, Atwood sat at a table with her friends in a rustic banquet hall, with strings of white lights hanging from the rafters. At the front of the room, Moss introduced a video of Ottawa Impact candidates on the campaign trail. There were pictures of smiling children, pickup trucks and American flags flapping in the breeze. In the background a Christian contemporary music star sang: “We’re the generation that has to make a choice/ Will we push against this evil or will we watch while it destroys?”

Most of the parties began to break up around 11 p.m., before all the precincts had reported. Barry headed home with a comfortable lead over Gretchen Cosby, a 60-year-old former nurse who had been inspired to get into politics by her false belief that Democrats had stolen the 2020 election. Around midnight the results posted online. Barry won with 63 percent of the vote.

The three Ottawa Impact candidates running for countywide office — prosecutor, sheriff and treasurer — lost to more moderate Republicans by about 20 percentage points each. Moss, Ottawa Impact’s co-founder, easily defeated his primary opponent by 14 points.

But his movement, which in January 2023 controlled eight of the 11 board seats, had suffered a devastating blow. After Tuesday’s results, they would, at best, retain just four.

“Their majority is gone,” said a relieved Poehlman a little after midnight. Her preferred candidate lost to Moss, but she and her friends didn’t let the defeat dampen their late-night celebration.

“That’s awesome,” said Janet Martin, a Democrat sitting next to her.

“It’s good for our county,” added Judy Bergman, a former Republican.

A new era

The next morning the people of Ottawa County awoke and started trying to make sense of what had happened the previous night. Atwood didn’t see the results, which included her own loss, as proof that Republicans had grown weary of Ottawa Impact’s hard-line politics. Instead, she blamed Democrats who crossed over and voted in the Republican primary for her group’s defeat.

“My Republican election was taken from me by Democrats” and wealthy donors, Atwood said. “Not every best candidate wins. That’s just how it is.”

Moss vowed that despite the results, he would never moderate his message. “The majority does not dictate morality,” he said in a statement posted to Ottawa Impact’s website. “There are consequences to abandoning truth and abdicating freedom.”

Justin Roebuck, Ottawa County’s clerk and a self-described conservative Republican, had sought to remain neutral in his local party’s civil war. He defended the integrity of the voting system that he oversaw but tried to win over the skeptics and election deniers in his party with good humor and civility. On Wednesday evening he invited about 50 of the county’s Republican leaders to a “unity” party at a brewery in Holland, Ottawa County’s largest city.

The gathering brought together all flavors of Ottawa Republicans. Josh Brugger, who won the GOP primary for relatively moderate Grand Haven’s commission seat, described the previous night’s results as a “multi-partisan” victory over Trumpism.

“When radicalism reared up, we all united to put it back down,” he said. He stood only a few feet away from Moss, who was wearing a light-colored sports coat over a campaign T-shirt that bore his name, spelled out in all capital letters.

Roebuck, who had been up late overseeing the election returns, was working on three hours of sleep when he took the microphone and addressed the crowd.

“Frankly, this has been a challenging and contentious time,” he began. Roebuck never mentioned Trump. Instead, he invoked Ronald Reagan, whom he described as a “man of principle,” and urged his fellow Republicans to come together in November to fight for the values that they shared — limited government, personal responsibility, fiscal restraint.

“We do have a lot to fight for and there are clear, clear differences,” he said, referring to the upcoming presidential contest in his critical swing state and a competitive campaign for an open Senate seat. At the county level, Republicans hope to prevent Democrats from adding any more board seats to the two they currently hold.

Barry, who came dressed in a shirt that featured the Statue of Liberty, fireworks and busts of Frederick Douglass and the Founding Fathers, said he wanted to find a way to work with Moss and the three other Ottawa Impact Republicans on the county board.

“Nobody was conquered last night,” he said. “We all live here. We’re all neighbors.”

There were 148 days remaining until the new board members would be sworn in and a new era of Ottawa County politics would begin.