“President Trump, as you know, the FBI says overall violent crime is coming down in this country.”

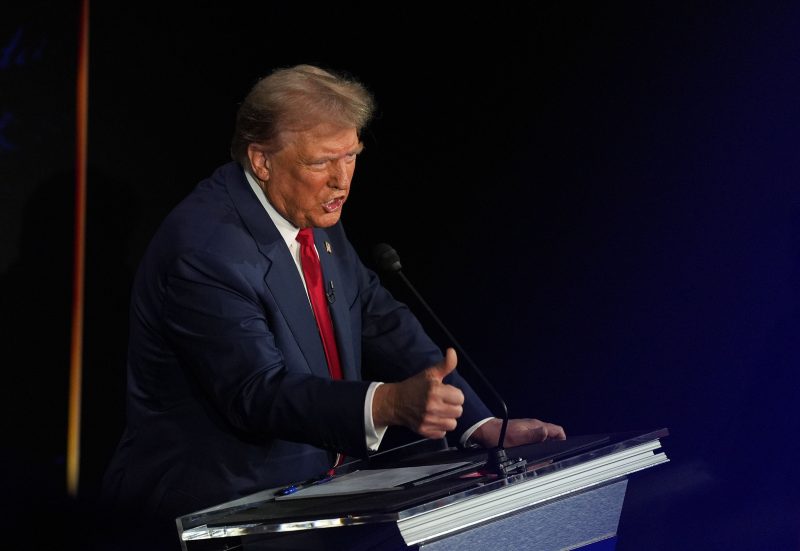

— David Muir, ABC News moderator at the presidential debate, Sept. 10

“MASSIVE NEWS! The Department of Justice just released brand new Crime Data showing I was absolutely and completely right at the Debate. In fact, the Data is even worse than we could have ever imagined. Compared to 2020, Violent Crime is up nearly 40 percent, Rape is up 42 percent, Aggravated Assaults are up 55 percent, Violent Crime with a weapon is up 56 percent, Violent Attacks on strangers are up 61 percent, Car Theft is up 42 percent, and the most serious forms of Violent Crime are up 55 percent. Our Cities are UNDER SIEGE. And this does not include the Migrant Crime and Migrant Rape spree that has overtaken our Cities in recent months. Kamala Crime is destroying America, and gangs are taking over!”

— Former President Donald Trump, in a post on social media, Sept. 12

When Muir fact-checked Trump during the debate with Vice President Kamala Harris, Trump dismissed FBI crime figures. “They were defrauding statements,” he said. “They didn’t include the worst cities. They didn’t include the cities with the worst crime. It was a fraud.” Then, two days later, he claimed that a new Justice Department report, the 2023 National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), showed he was right.

In our debate fact check, we noted that Trump relies on NCVS data, but given the new report, the dispute over the numbers seems worthy of a deeper dive. This is a good example of how politicians highlight government reports — and cherry-pick from them — to shape their rhetoric.

The Facts

All crime data has its limitations. The FBI issues the Uniform Crime Report based on crimes reported by police departments. But because the FBI in recent years changed the way it collects data, not all police departments participate. The 2022 report included crimes reported to 80 percent of the nation’s law enforcement agencies by the public.

Contrary to what Trump said at the debate, that may not be much of a problem. The crime rates reported by the FBI would only be affected if crime in the missing cities were significantly higher or lower — and there is little evidence that’s the case. “It’s only relevant if it would shift the averages,” said Ernesto Lopez, senior research specialist at the Council on Criminal Justice, a research institute. “We could have half of the cities missing. It doesn’t matter if they don’t shift the data.”

The FBI has not released full 2023 data yet, but a June quarterly report showed violent crime decreasing 15 percent year over year. That was the report cited by Muir.

The Council on Criminal Justice examines monthly crime rates for 12 violent, property and drug offenses in 39 American cities that have consistently reported monthly data over the past six years. In July, it reported steep declines in homicide and most other violent crimes back to levels that predated the pandemic.

At the same time, many crimes are not reported by the police. Arrest rates have fallen, and fewer people even bother to report crimes. Victims tell the Justice Department they only report about 45 percent of violent crime and 30 percent of property crime.

The victimization report attempts to fill in that gap by surveying Americans on crime they have experienced. Households are selected to be a representative sample of the United States, and for 3 ½ years they are interviewed in person every six months about whether the household had been a victim of crime since the last contact.

But the NCVS has its own drawbacks. Since homicide victims cannot be interviewed, the report does not include homicide — and many criminologists say murder rates are the best indicator of violent crime. The survey does not interview people who are homeless or in institutions such as prisons, jails and nursing homes; it also does not include crimes against people younger than 12.

All of Trump’s figures in his post compare crime rates, as listed in the victimization survey, in 2023 with rates in 2020. That’s the last year of his presidency, so in ordinary circumstances that might make sense. But this is a survey — and during the pandemic it was more difficult for researchers to conduct it. Normal field operations were suspended after March 2020 and people had to be interviewed by phone for most of the year, so criminologists urge caution with the figures.

The reports, when issued, measure crime rates over a 17-month period, so they cover more than the year of the report. For instance, the 2020 report covered July 1, 2019, to Nov. 30, 2020, and the 2021 report covered July 1, 2020 to Nov. 30, 2021. Two reports — 2020 and 2021 — thus were affected by covid.

Like any survey, the NCVS is an estimate and has a margin of error. For instance, the reported crime rate of 16.4 per 1,000 people in 2020 had a 95 percent confidence level of being between 14.84 to 17.94. The margin of error increases even more in subcategories such as sexual assault and auto theft

Moreover, with so many people sheltering in place, fewer people in 2020 were likely to be robbed, raped or violently attacked by a stranger. After the George Floyd murder in May 2020, violence erupted in many cities and homicides sharply increased. Trump, as he campaigned for reelection that year, frequently highlighted the increase in homicides and shootings in “blue” cities such as New York. But that kind of problem would be reflected in the FBI reports, not the NCVS.

“It’s problematic to use 2020/2021 (the pandemic) as a baseline from which to judge current crime rates. Covid profoundly changed daily life in a variety of ways that impacted crime,” said Jillian Turanovic, a sociology professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder and an expert on crime victimization, in an email. “With social distancing restrictions, more people stayed home during the day and were not out in crowded public spaces. As a result, rates for several opportunity-based, instrumental crimes decreased in 2020 and 2021 — crimes such as robbery, burglary, and theft. However, Covid was also a stressful and traumatic time that coincided with increases in particular forms of interpersonal violence and homicide in several major U.S. cities.”

Turanovic added, however, that “the NCVS data remain the best and most reliable national source of victimization data that we have at our disposal — especially on crimes not reported to the police.”

Still, for at least two key reasons — both related to the pandemic — 2020 is a not a good year to use as a baseline. Jeff Asher, a crime analyst and consultant, says he simply ignores the 2020 and 2021 NCVS data because those years were too hard to survey.

Look what happens when we examine the NCVS categories highlighted by Trump but use 2019 as a baseline for comparison with 2023, using the rates of crime per 1,000 people.

Violent crime: 7 percent increase (vs. Trump’s 40 percent)

Rape/sexual assault: no increase (vs. 42 percent)

Aggravated assault: 22 percent increase (vs. 55 percent)

Violent crime with a weapon: 33 percent increase (vs. 56 percent)

Violent attacks on strangers: 41 percent increase (vs. 61 percent)

Car theft: 56 percent increase (vs. 42 percent)

Serious form of violent crime: 19 percent increase (vs. 55 percent)

The overall rate for violent crime (22.5 crimes per 1,000 people in 2023 vs. 21.0 in 2019) is not statistically different from 2019 to 2023, said Kevin M. Scott, the acting director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in a statement. Except for rape, we see an increase in violent crime in the subcategories, where the margin of error is higher, though not nearly as much as Trump claims in all but car theft.

But even this is cherry-picking, as crime trends need to be observed over longer periods of time. If you look at overall trends over the last 10 years, the rate of violent crime has basically remained steady, within the margin of error of the survey. And overall, violent crime rates are much lower than the 1990s.

As Turanovic put it: “While there are some minor discrepancies in trends between the NCVS and FBI data when looking narrowly from one year to the next, in my view, the data sources are still telling a similar story: both tell us (1) that the nation’s violent crime rate is substantially lower than it was in the 1990s, (2) that violent crime rates (based on most recent data) are largely on par with where they have been over the past decade, and (3) that there is no evidence that violent crime rates are ‘soaring,’ or as Trump said in the debate, ‘through the roof.’ Even at their recent peak in 2020, homicide rates in most cities were still half of what they were 25 years ago.”

One problem with both the FBI report and the victimization survey is that it takes a long time for the data to be collected and published. Asher’s organization has created what it calls a Real-Time Crime Index that collects data from about 300 police agencies covering a quarter of the U.S. population, including 29 of the 30 biggest cities. The data are displayed as a 12-month rolling sum.

From 2018 through June of this year, the index shows violent crime is flat. Homicides spiked in 2020 and peaked in 2021 but are now coming back down. Rapes have fallen slightly. Aggravated assaults also spiked in 2020 but have since dropped. Motor vehicle thefts soared in 2021 but have started to show a decline this year.

The Bottom Line

Be wary when politicians cite crime statistics. There is no perfect metric, as there are flaws in both the FBI report (not all crimes are reported) and the victimization survey (it’s an estimate with a margin of error). Dating crime data from 2020, as Trump does, is especially problematic because the pandemic makes it difficult to trust the data that was collected.

But there’s no debate over this fact: Violent crime today remains much lower than it was in the 1990s.

(About our rating scale)

Send us facts to check by filling out this form

Sign up for The Fact Checker weekly newsletter

The Fact Checker is a verified signatory to the International Fact-Checking Network code of principles