N.H.’s primary pushed the GOP to fix acid rain. Climate change is another story.

CONCORD, N.H. — Thirty-six years ago, Republicans in the first-in-the-nation primary battled to prove they had the deepest commitment to the day’s most contentious issue: the acid rain poisoning New Hampshire’s lakes, rivers and forests.

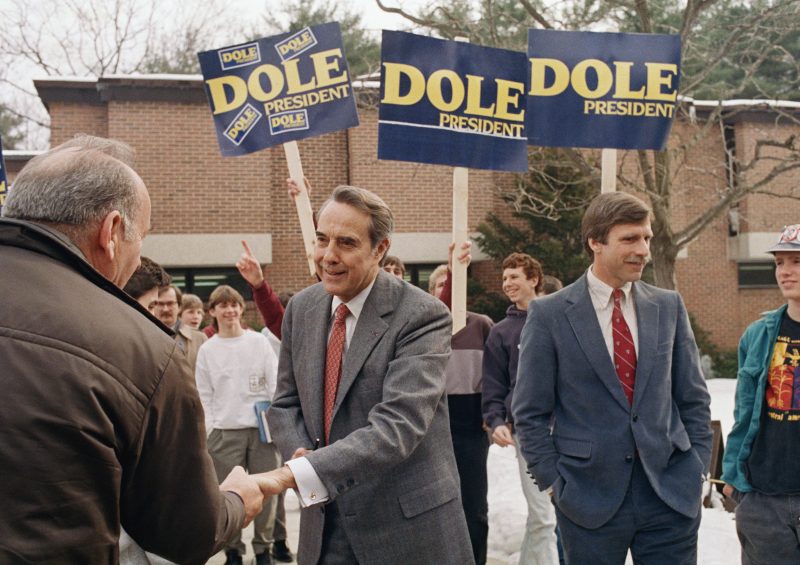

George H.W. Bush promised to restore his party’s conservation ethic and curtail pollution. His top competitor, Senate Republican leader Bob Dole, vowed to quickly pass an acid rain bill. The state’s voters and its Republican governor, Gov. John H. Sununu, had elevated the issue before the primary vote that helped propel Bush to the White House, where he followed through by signing legislation that has curtailed acidity in New Hampshire by 84 percent to date.

“This is one of the most significant environmental science and policy success stories of our time … and New Hampshire is its birthplace,” Anthea Lavallee, executive director of the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation, which supports the facility where acid rain research has been conducted, said at an environmental forum here on Thursday.

Now, however, as New Hampshire faces the much broader threat of climate change, Republican candidates in the state for Tuesday’s primary are barely mentioning the issue — and when they do, it is often to play it down.

Nikki Haley advocated pulling out of an international climate deal as President Donald Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations; she has said “man-made climate change is real, but liberal ideas would cost trillions and destroy our economy.” Trump calls climate change a “hoax.” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has said he supports efforts to address the impact of hurricanes and flooding, but he rejects “the politicization of the weather.”

Republican Gov. Chris Sununu, the son of the former governor, said in an interview that he sees no comparison between dealing with acid rain and climate change.

“Climate change is a completely different story,” the younger Sununu said. “There’s a lot of politics behind that kind of socialistic approach, that green New Deal type stuff that costs trillions of dollars.”

But to environmentalists in both parties here, the analogy is clear: the bipartisan framework that significantly reduced acid rain is exactly what’s needed to deal with climate change.

The story of how New Hampshire conservatives once forced action on acid rain stands in stark contrast to the party’s environmental policies today and helps illustrate a seismic shift in party politics in America, with fewer chances for small early primary states to effect radical change on major issues.

“There’s been almost no discussion” of climate change by Republican candidates in the state’s primary, said former U.S. Sen. Judd Gregg (R-N.H.) who played a leading role in the 1990 Clean Air Act that dealt with acid rain. “People in New Hampshire do vote the environment aggressively. This is a state built around environmental protection.”

For years, New Hampshire residents were growing increasingly alarmed by the pollution causing mass die-offs of aquatic life in lakes and rivers and the deterioration of vast numbers of trees. The environmental devastation harmed everything from the forest industry to tourism, blotching a region known for its Currier and Ives landscapes.

As scientists scrambled to understand the exact causes of the phenomenon, they turned to the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, a patch of the White Mountain National Forest. Gene Likens, who in 1963 was a 28-year-old scientist, led a team of researchers that eventually confirmed the acidity was caused by the sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions from Midwestern power plants, carried by air currents and deposited into the state’s lakes, rivers and forests. Likens’s team determined that a primary solution was to greatly curtail pollution from the coal-fired power plants and other sources.

Lawmakers in the state demanded action. By the early 1980s, 197 of 199 New Hampshire towns had voted in favor of regulating acid rain emissions, a remarkable standing for a state that had New England’s weakest environmental laws. Gov. John H. Sununu signed a state bill in 1985 requiring emission cuts, boasting of his “stringent acid rain control law.”

Three years later, the problem of acid rain took center stage in the New Hampshire primary, and candidates in both parties responded by vowing to take federal action. Dole warned there was no time to waste dealing with acid rain and was quoted in the New York Times saying, “We don’t have the luxury of waiting until we get details on the extent of the potential problem.”

Bush, then the vice president, was eager to define himself on the issue after the lack of action by President Ronald Reagan. With the elder Sununu serving as co-chair of Bush’s New Hampshire campaign, Bush vowed to reduce emissions. After winning the primary and the nomination, he sought to portray himself as a stronger defender of the environment than the Democratic nominee, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, whom he criticized over the pollution in Boston Harbor. After a fall speech in which he once again vowed action on acid rain, Bush spoke of his “conservation ethic,” and said: “I am an environmentalist, always have been.”

After Bush was elected president, and Sununu became White House chief of staff, he convinced most Republicans in Congress to vote for the legislation to clean the air and curtail acid rain. The legislation capped emissions but allowed companies to trade credits primarily among coal-fired power plants, sparking innovation that reduced the cost. Known as “cap and trade,” the practice was embraced by Bush and other Republicans as a market-based solution.

While opponents predicted the legislation would be an economic disaster, it reduced acidity at much lower cost than expected, according to environmental scientists. Opponents calculated the legislation would cost $1,500 to reduce a ton of sulfur emissions, but the actual price ended up being about $15 a ton, Likens said.

Bush later said that “public servants have an obligation to try to leave the earth better than we found it,” as he told the Boston Globe in 2010. He recalled a friend had suggested he view “the environment as creation,” leading Bush to conclude, “It gives you a new appreciation for this issue and why it matters to Republicans and Democrats alike.”

Despite its success dealing with acid rain, the 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act mostly failed to address emissions that cause climate change, even though there were warnings about the issue at the time.

The result of both the success and failure of that legislation is evident today at the Hubbard Brook research facility, a 7,800-acre site supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, where scientists conduct one of the country’s most extensive studies of air, water, soil and other parts of the ecosystem.

Hubbard Brook researchers have measured the 84 percent decline in acidity, according to Likens — a remarkable decrease from the peak around the early 1970s. But they have simultaneously documented that last summer, the site experienced the warmest temperature since measurements began in 1956, according to Lindsey Rustad, acting director of the Agriculture Department’s Northeast Climate Hub. The mean annual temperature increased by 3.6F (2C), which compares to an average global surface temperature increase of 2F (1.1C) over the same period, Rustad said.

For New Hampshire, Rustad said, the increased warming has meant longer growing seasons, warmer winters, less snow, shorter periods of lake ice and more heat waves.

“Climate change is unquestionably the biggest environmental crisis we’re facing right now,” Rustad said. “2023 was a warning.”

Climate change could be solved “just like we did with acid rain,” Rustad said.

But the political divide over that kind of action is evident on the campaign trail for this year’s primary in New Hampshire. Trump, the leading GOP contender in polls, pulled the United States out of the international climate change treaty — a move that Haley, one of his top rivals, had also backed as U.N. ambassador.

The Trump, Haley and DeSantis campaigns did not respond to requests for comment. Gov. Chris Sununu, who has endorsed Haley, said she did the right thing in backing the withdrawal from climate accord because he said that agreement let big polluters such as China off the hook. Many New Hampshire residents, he said, are more concerned about the cost of heating their home than enacting new regulations.

The political climate — not just the ecological climate — has also changed significantly since his father was governor.

“George H.W. Bush did a great job of making sure that something got passed” on acid rain, the younger Sununu said. But he said climate change activists “have the extremist approach that the world is ending in 10 or 12 years or whatever these folks have told us, and have massive policy changes or, or catastrophic events are going to happen, which, again, is an extremist approach.”

President Biden, who is not on the ballot in New Hampshire because he opposed it remaining the first primary, has strongly supported efforts to curtail climate change.

Sixty-one years after Likens led the discovery of acid rain, he appeared Thursday at the Youth Forum on Climate and Clean Energy, where he discussed how his experience can be translated into action on global warming. Despite what he called his discouragement over lack of political consensus on addressing climate change, Likens said he has to remain optimistic — especially given his own experience in the discovery of acid rain and then seeing the crisis fade into the background.

“It took 27 years from the discovery of acid rain in North America to the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments. It took another 34 years to today to reduce it to the near background level that it is today,” he said. “It’s very rare that a scientist is there from discovery to reaction. It takes a long time. It’s not right, but it does.”